Street Photography and the Los Angeles Riots of 1992

A reflection on my experience as a street photographer during the 1992 Los Angeles Riots in light of the racial tensions in 2020.

Street photography has always been a passion of mine. When I first picked up a camera in high school, I took to the streets to find my subjects. The key to being a good street photographer is being able to be inconspicuous. It is difficult walking around with a big obvious camera. A small camera like the Fuji X series is a great camera for it. In the past I have had a small Contax camera. Sometimes you shoot from the hip without even looking through the lens because you don’t want to be noticed. You want to test your settings ahead of time, so you are always prepared to capture the moment in the moment.

The year of 2020 has seen the Black Lives Matters movement explode. Since February, there has been a deluge of race-related wrongful deaths (Ahmaud Arbery February 23, 2020, Breonna Taylor March 13, 2020 and George Floyd May 25, 2020). As a result, the tensions within the community have been building all over the country and the world. There have been peaceful protests as well as violence and public outrage on all sides of these unfortunate events. A lot of my younger photographer friends took to the streets to document these protests, and I have been seeing all of these beautiful photographs popping up on my Instagram feed. I love it. These photographs are powerful and show the truth of the moment. It brings me back to 1992, the LA Riots, when there was no Instagram and my friends and I were shooting on film. These were also not peaceful protests, it was raw public outrage and pandemonium. I didn’t get out there to document the Black Lives Matter protests, but I did get out there in 1992.

I was finishing my sophomore year at USC, located in South Central Los Angeles, when the LA riots broke out in April 1992. I was caught up studying for finals, which were the following week; so I didn’t really know what was happening around me until I got home and watched the news later that night. I knew something strange was going on my way home as I passed a couple of random buildings that had raging fires. The strange thing was that there were no fire trucks or even sirens in the distance. I saw one guy with a garden hose trying to put a fire of a storefront out. The city seemed abandoned while several fires were raging all around. What the hell was going on, I wondered.

There was no question at the time that this was an historic moment. So I picked up my camera and took to the streets of South Central LA. It was the third or fourth day that my photographer friend from Cal Arts, Marie Alpert and I drove down to the Crenshaw district and shot as much film as we had on hand. I used Tri-Ex and Ektachrome 100 (which I cross-processed and later converted to Black and White).

In 2017, I showed a series of these photos in the LA Open at TAG Gallery and won honorable mention. It shows how often times especially documentary photography has more significance and value as time goes on. That is why it is very important to archive your work and sit on it until the time ripens for the moment to be reflected upon and appreciated. As time goes on, whatever history we have documented and preserved becomes more and more priceless because the moment is no longer there, and we as a society have the need to analyze and learn from it.

I have been noticing how rhetoric justifying racism, white supremacy and xenophobia have been ramping up in the past three and a half years since the election of Donald J. Trump in 2016 and how this president has consistently stoked the flames of racial polarization. Suddenly, incendiary dehumanizing language has become socially acceptable at the highest levels. It is eerily familiar since I studied the rise of the Nazi party in 1933 and have written about it extensively. I have visited Auschwitz as well as other concentration camps in Poland and Germany. Nazism began with the use of racist stereotypes in language and then escalated to policies limiting the civil liberties, to the institutionalization of the murder of more than 6 million human beings.

Hitler campaigned on a plan that would boost the economy and better Germany. It is very similar to Trump’s campaign slogan “Make America Great Again.” The Nazi “plan” was to maximize profit for the Germans by reducing certain humans categorized as “sub-humans” to raw materials (human ash used as fertilizer, shaved human hair used as insulation, human fat used as soap and teeth reduced to gold fillings.) No, I am not making this up. So it is a slippery slope from racial slurs to fascism, authoritarianism and genocide. One cannot help but notice a similarity in the philosophy of someone like Texas Lt. Governor Dan Patrick when he suggested on live television that grandparents could be sacrificed for the economy in context of the Covid-19 pandemic, which aired on the Fox News program “Tucker Carlson Tonight” (March 23, 2020).

The normalization of death of our fellow citizens during the covid-19 pandemic has only added to the gradual tendency of judging certain people as less than or dispensable in some way whether it’s the elderly or whether it is someone with underlying health problems or whether it is a person of a minority. I have watched as the groups, disproportionately affected by the virus, have been systematically devalued and judged responsible somehow for having an adverse reaction to the virus, that “they would have died anyway because of x, y or z.” This growing belief that some lives are worth less than others bothers me, and I hope it bothers everyone reading this. The value of a human life is priceless, no matter what color, creed, shape or age that life is.

Hitler used nationalism to uplift German citizens’ spirits and manipulate them into believing that they deserved more meanwhile preying upon their fears and ignorance, while at the same time inflating a false sense of Nationalist pride. These extremist views were not automatically accepted. Nazis eased people into what later blossomed into full-blown genocide. It began with small policies over years, which gradually developed into more active violent policies. Over time, these gradual steps prepared people for the worse. The mentality was that each step was a little worse than the previous; so people began to believe it was okay.

Hmmn, this again is beginning to sound very familiar as I watched reputable journalists being shot with rubber bullets, concussion grenades and sprayed with tear gas on live TV from Minneapolis last week. I thought things could not get much worse, but then then a few days later in Washington D.C. a peaceful crowd of protesters, a priest among them, was tear gassed and sprayed with rubber bullets in order for our President and his entourage to take a photo op with a prop bible in front of St. John’s Episcopal Church across from the White House.

In 1992, after the not-guilty verdict in the trial of the police officers who beat Rodney King on video tape was handed down in Los Angeles, unbeknownst to me, anarchy was about to descend upon the city for several days.

Approximately six months before the riots, I had my own experience with police brutality and LAPD. I was driving with three friends on a quiet street in the Fairfax/Beverly neighborhood of Los Angeles at night. I made an illegal turn, and police stopped us in an abandoned alley. We were told to get out of the car with our hands up. We all followed the orders. There was one male in the car, and three females who were all my friends. When the only male exited the car, hands up, he was immediately hit in the face by one of the police officers and then brutally beaten with nightsticks and kicked while lying in surrender on the ground. This male friend of mine did absolutely nothing to provoke this attack. It was immediately clear that this was not a typical traffic stop. I was never asked to present my driver’s license or registration. I knew right away these police officers were just looking for an opportunity to unload their rage on someone. I am not even sure if they had witnessed my illegal turn. I think we were just in the wrong place at the wrong time. Meanwhile, we were all white and we still suffered police brutality. So while I don’t think police brutality is limited to one’s race, I can imagine it might be even worse in combination with racial profiling and the normalization of racial stereotypes.

I distinctly remember my own personal experience of police brutality occurred somewhere in between the Rodney King incident and the Rodney King trial. Shortly after the verdict and riots occurred, two FBI agents showed up at my house to question me about the incident with my friend. They interviewed me on tape to record my recollection of events. There had been many reports of police brutality in Los Angeles at the time and a federal investigation was being conducted. Several times during the interview, the FBI agents attempted to convince me that my friend must have given the officers cause to attack, maybe my friend put his hand near his pocket and that maybe the cops thought my friend was reaching for a weapon. I told them absolutely not.

For a long time after that incident I lived in fear of the LAPD. To a certain extent I still have fear. They have guns and are trained to react with violence. We, as everyday civilians, do not have guns (for the most part) and are not trained in violence. When it is your word against a police officer, the police officer will always receive the benefit of the doubt in a court of law. Therefore, bad cops have very little repercussions on their behavior.

My attitudes about the LAPD have changed a lot over the past twenty-eight years. I have gone from feeling hostile to being terrified of the power they hold to being sympathetic to the LAPD for the job they have as a force of 10,000 trying to keep peace among 10 million. In 2013, I met LA County Sheriff Lee Baca when he gave a talk to a group of college students at Loyola Marymount University. He spoke about how LAPD had learned something important from the LA Riots of 1992. They realized police must work with the community to gain trust. Policing is more effective if the community works with LAPD to ensure peace. Hostile relations with the community through brute force creates a more dangerous situation for everyone: community and police officers alike. In a city like Los Angeles, the police force depends upon the majority of the community to uphold the law in order to effectively do their job of protecting citizens. If a large portion of the community decides to disobey the law (as in Los Angeles Riots of 1992), the police do not stand a chance. The police feared for their lives in April 1992 when the riots broke out, and that is why they were no where to be found when the fires and looting broke out. Baca explained that LAPD was working very hard to ensure this would never happen again by making many reforms in their policies. Ironically, Lee Baca is now serving a 3 years in Federal prison for obstructing an FBI investigation of prison abuses. I don’t know much about that, but what he said about policing that day made a lot of sense, and I have a lot of respect for what he was trying to achieve in terms of police reform.

Well, here we are in 2020 and in the aftermath of several race-related killings, we are experiencing a mixture of peaceful protests, riots, looting, white supremacy groups showing up with guns and creating mayhem in cities nationwide. These protests have grown beyond our national borders to places like London, Paris and Berlin. Young people, especially, seem inspired to speak up for this cause. To complicate matters, we are still in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic and these protests and conditions of people crowding together and being tear gassed, create unsafe conditions for the virus to pick up speed and spread at a faster pace. In the early days of the unrest, the police were caught on camera in many cases beating peaceful protesters, gassing them and shooting them with rubber bullets and concussion grenades. So it appears this issue has only gotten worse than it was in 1992.

Our president and others such as Senator Tom Cotton have threatened to use the 1807 Insurrection Act to deploy active U.S. military forces on American citizens. Attorney General Barr has suggested charging some mayors with sedition in he cities where the civil unrest is taking place. It is amazing to see how our society has unraveled so rapidly in just a few days, weeks and months. On the other side, many police officers and National Guard members have “taken a knee,” alongside of the protesters. The Los Angeles City mayor, Eric Garcetti, has also announced a $150 million defunding of the LAPD in order to divert the funds to social services to underfunded communities. The mayor of Washington D.C. Muriel Bowser has painted “Black Lives Matter” in big yellow block letters on the black asphalt of the street leading to the White House and has renamed the place in front of St. John’s Episcopal Church “Black Lives Matter Plaza.” Many other cities have followed suit and painted their own “Black Lives Matter” murals.

What I learned from 1992 is that no issue is as simple as first appears—especially when it has to do with urban landscapes, politics and social realities. Police are human beings just like you and me. They are not monsters. Of course there are some hardened violent criminals out there, lunatics and bad people. I do think most cops are trying to do their best to protect the community and themselves. It is a shame that there are some cops, who are simply bullies or sociopaths in a uniform. Those cops give the good cops a bad name. Unfortunately, the legal system is not equipped to handle these bad apples.

I can sympathize that policing is a very stressful job because it places your life in constant danger. PTSD is something many police officers suffer as a consequence of their job. When police enter a crime scene they often do not know much about the details of what is going on. They are walking into volatile and dangerous situations on a daily basis. Do not get me wrong. I am not excusing the minority of officers who use the power of their uniform to bully and intimidate. This behavior clearly needs to be scrutinized and called out, and there needs to be a set of guidelines to arrest this behavior. I know in Los Angeles, most of my friends, who have lived there as long as I have, either have had personal experience with police brutality or know someone who has experienced police brutality. So police brutality was very commonplace especially before 1992.

There is one thing I know is it not in your favor to antagonize a police officer. If you want to be treated with respect, you must be very deferential. If you fail at that, you are more than likely to be treated with force or arrested for spurious charges. Police have a difficult job as it is, and they do not have much patience for back talk. So you are really asking for it, if you choose to react that way when confronted by an officer. Because of the nature of their jobs, police defense mechanisms are tuned up to the maximum volume. If you try and provoke a police officer in any way, you are playing with serious fire.

The most important lesson for me from the 1992 Los Angeles riots is we cannot take social order for granted. One incident like the Rodney King verdict can set off a chain of events leading to lawlessness. In these cases, the police cannot effectively do their jobs, and we, the public, become even more vulnerable to violence. Police and the community depend upon one another. When this trust deteriorates, so does public safety. Having a President and an administration who actively throw accelerant on these tensions instead of using healing salve has the potential for even more disastrous results.

The most terrifying part of the 1992 LA Riots was that the police and fire department retreated. They knew they were outnumbered. A white trucker, Reginald Denny, was pulled out of his truck and almost beaten to death on the first day of the riots by an angry mob. He didn’t have a radio and had no idea he was driving into a riot when he exited the freeway that day. He was in the wrong place at the wrong time. Buildings on every corner were burning down, and the most remarkable thing was that no one was coming to the rescue—no fire department, no police. Looters were running through the streets, arms full of purloined items, scavengers could be seen picking through recently burned down shops. A female photographer friend of mine, white, was beaten while taking photographs of the riots and lost her hearing in one ear as a result.

After a few days of Armageddon, the National Guard was called in and tanks and officers carrying machine guns patrolled the streets. The sky had become dark gray from smoke, and the sun rescinded to a smoldering orange dot burning through black. The air was thick and heavy. There was silence, uncertainty, anxiety, fear and loathing. Once chaos like that is unleashed, the terror associated is very hard to forget. You will forever remain aware of the potential for civil unrest there bubbling beneath the surface of discontent, wealth disparity and poverty in a city, just waiting to explode at any given trigger. I think the LAPD probably understands this phenomenon better than anyone. Since 1992, LAPD has worked very hard at reforming and holding police officers accountable. Six weeks after the riots, Proposition F for police reform was passed. This law ensured civilian oversight and made building trust with communities a priority. This was passed not only because it was in the interest of public safety but also because it was in the interest of police safety as well. LAPD is not perfect by any means, but I think they can be held up as an example to other cities and police forces across America who are still struggling with accountability.

I don’t think police reform is an issue about taking sides: either Black Lives Matter or Blue Lives Matter. It is an issue where trust needs to cultivated within the community and between communities and to validate our common desire to live in safe, friendly neighborhoods with relative peace and harmony. At the end of the day, Los Angeles is my community and these riots were part of the history and landscape of what it means to me to be an Angeleno. It is all part of the complex patchwork we call life.

Challenges of Shooting in Remote Locations

Challenges of Shooting in Remote Locations

Challenges of Shooting in Remote Locations

In December 2013, I was asked to shoot the 2015 Voda Swimwear catalogue in the British Virgin Islands. The shoot involved traveling on a catamaran for two weeks and shooting on remote islands.

What made it more challenging was that it would be a a bare bones shoot with a very small budget considering what was to be accomplished. I accepted the job because of my love for adventure and sailing. The clients are also good friends. Yulia, the designer, I have known practically since she moved to the U.S. with her husband Dustin, a former marine, from Kyrgyzstan.

Even though this job was not a big pay day for me, the experience it gave me was invaluable. We had not only had a blast shooting, relaxing and exploring in our downtime, it was also one of the most challenging shoots of my career both physically and strategically.

For several months before the shoot, I thought about what kind of lighting equipment I would use. I wasn’t sure if I would have an assistant besides Dustin, so weight was a factor. I also knew from years of shooting their catalogues before, that I could expect to have to shoot about 80 bikinis. Having been on many small craft boats, I also knew space would be confined so size and portability was also a factor. I am loathe to bring equipment I am not absolutely sure I will use.

The week before the shoot was troubling because the weather forecast was clouds and rain. It was only on the day we actually left that I finally decided I was going to take a chance and rely mainly on two photoflex reflectors. I brought my Canon 600 EX flash and 2 Quantum 400 strobe units. I left my Profoto 7B kit at home because of the weight and foreseeing it could be a problem transporting it on a dinghy, etc.

When we arrived it was stormy and wet. I was starting to wonder if I had made the right decision not to bring the Profoto to fake some sunshine.

It turned out I was awarded an assistant afterall. This was a real blessing because I can’t imagine completing this job without one.

I could not have hoped for someone better either. We met Dan, an ex U.S. Force Recon Marine, hanging out on the dock with a backpack and asked if he would be willing to come along. After a couple minutes of thinking, he gladly jumped aboard joining our adventure. Not only was he a great assistant, but one of the most authentic and unique human beings I have ever had the pleasure of meeting.

None of us had been to the British Virgin Islands before, so Dan also acted as an expert guide, deckhand, cook. . . . You name it. He even taught me how to scuba dive at “playgrounds” near Sandy Spit.

This was a working vacation for all of us. We would be gone for two weeks and decided to divide the shoot across five half days to be shot early in the morning at sunrise to avoid the scorching temperatures and also so we would have afternoons to play around in the sun and water.

The lighting conditions would have been better in the afternoon since the leeward side of most of the islands were facing West and the open sea was facing East.

The weather and lighting conditions were less than ideal. In the morning we had to wait for the sun to rise over the mountains and then we had clouds drifting in and out for most of the day. At some points we even experienced light showers while shooting. Beyond this, the wind was an average of 18-24 knots, perfect for sailing but not so great for hair.

Our first day proved difficult. Mostly because there was some disagreement about where the best places to shoot. Also Dan had not yet come onto the job yet, so it was just Dustin and me. We were at a resort on Peter Island. It was beautiful, but the wind was so strong that it was impossible to get off more than a few shots.

The morning lighting on the leeward side of the island was cool and flat, and I had to use my Canon 600 EX flash to attempt to make the colors pop. I suggested to Dustin that we find an alternate location. Dustin agreed and we left for the adjacent Salt Island. Salt proved to have better lighting and wind conditions. We only shot half as many suits as I had hoped for that day (maybe 15).

We lost a lot of time because we had to sail to a separate location. By the time we arrived at Salt Island it was blistering hot and the heat exhaustion was starting to get to us. The good news was that we realized after that experience that we would have to think more carefully about which locations we would choose. We also decided to begin as early as possible (4:30AM) to avoid the sweltering sun. The reward for starting early was that we always had time to snorkel after a hard day’s work.

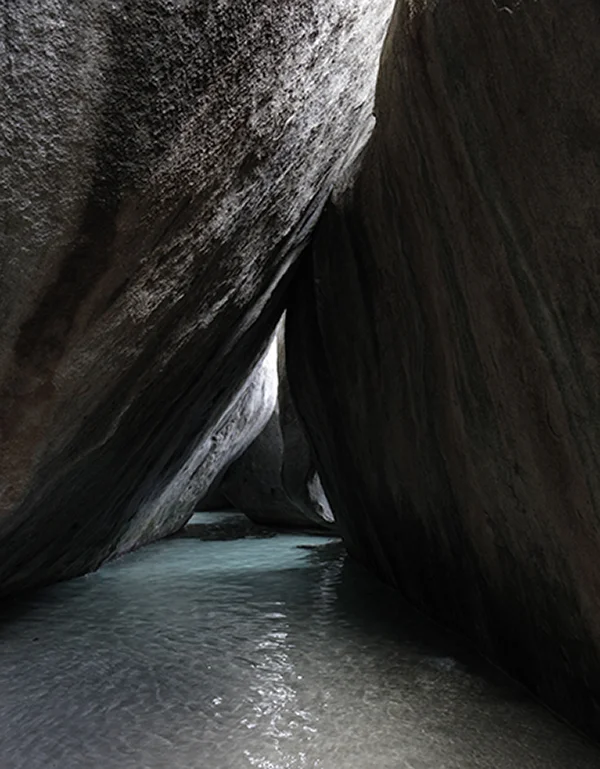

Our next shooting day was at the famous “Baths” on Virgin Gorda.

This was by far our most difficult day. We had disembark a rubber dinghy in 3 feet of water and carry our equipment and wardrobe to shore through waves somehow without getting it wet. Dustin and Dan did yeoman’s work that day. After our equipment was safely on shore, Dan and Dustin still had to carefully guide the dinghy by hand through some large rocks and drag it onto shore.

At this point, I was really glad that I did not bring the Profoto 7B along. However, even with all the trouble, the exquisite scenery made our extraordinary efforts well-worth it. I only wished that we could have spent an extra day there shooting. We had to hike through some serious rocks, but we found an amazing grotto nicknamed “the cathedral” because of the dramatic way the light leaks in.

Thankfully, we arrived super early before the tourists started pouring in, and we were able to shoot 3-4 suits using a combo of reflectors and the Quantums. I was beginning to worry that we were not getting enough work done each day.

This was also the most difficult day for me because I had been experiencing extreme tendinitis in my right forearm making it difficult to hold the camera. To make matters worse, after the shoot, we all went snorkeling at Devil’s Bay and I got separated from the group, getting lost. I could not remember where we had moored and ended up swimming for more than 2 hours before I found our boat, Ty Soizic (the name ironically means “Get Sober”—exactly what we were not doing most of the time).

To make matters worse, as is usual on a boat we experienced some technical problems with our engine and our wifi, so we had to head back to Roadtown to have the boat serviced.

We headed to Trellis Bay to experience local artist, Aragon’s, fullmoon party.

Dan is originally from San Francisco, but had come to BVI on vacation with his family and found a way to stay by working/ living as a WOOFER on Aragon’s organic farm up in the hills overlooking Trunk Bay towards Guana Island.

Here we discovered Arundel Rum from the Callwood Distillery, which is one of the best rums I have ever tasted.

After long discussion, we decided that Anegada, while the furthest island, would offer the best shooting possibilities. We even considered shooting two days there. We liked that Anegada has miles of stretching white sand beaches and turquoise water.

This is exactly the look the client was craving. The fact that the island is fairly flat also made morning lighting better because we did not have to wait as long for the sun to rise over mountains. Anegada was our most productive and easy shooting day.

We were able to use two reflectors for the whole day, allowing us to move quickly and shoot several suits (30) in a short amount of time. The lighting, besides clouds drifting in and out, was pretty consistent.

The stars at night in Anegada were incredible. We all were sad to leave this beautiful haven. But we decided our scenery options on the island had been maximized, and we only had two more days left of shooting. So we decided to make our way back to Tortolla to Soper’s Hole to celebrate Matt’s birthday.

Dan cooked up some crepes with Nutella and bananas for brunch, and we popped a bottle of champagne.

At this point we were more than halfway finished, and feeling entitled to a few days of relaxation. We went to a local dive bar and enjoyed to some live acoustic music, danced and mingled with the locals.

With one week left, our days were running short. So after much determination, we decided we wanted to split our time between Jost van Dyke and the Bitter End on Virgin Gorda, which had a couple of very nice yacht clubs to hang out during our free time.

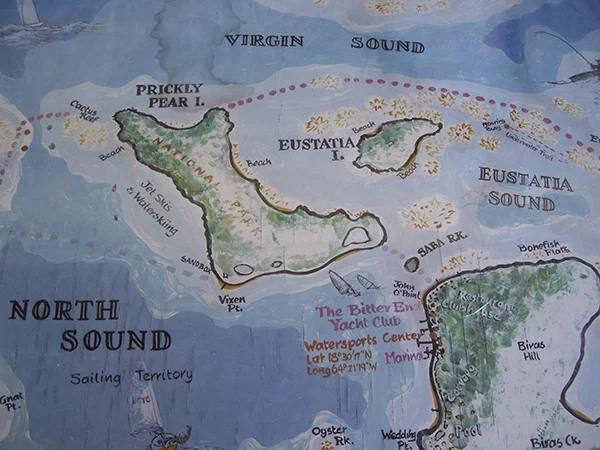

Our last two shoot days would be Sandy Spit, a small uninhabited island just off the coast of Jost Van Dyke and Prickly Pear Island, which was just off the coast of the Bitter End.

After spending a couple of days at Jost van Dyke scuba diving, swimming and visiting the local watering holes for Rum therapy—Foxy’s, Ivan’s and the Soggy Dollar, we anchored at Sandy Spit at about 4:30 AM. The day went without a hitch. Second to Anegada, this was our best shooting day.

On our last shot an older gentleman was lingering back and forth in our shot, when we finally realized this same older gentleman had been dancing the night away with our model Yulia at the Bitter End, just a few nights earlier. Had he been following us? We greeted each other and shot some group photos.

It turns out he was on 40 foot mono hull sailboat with seven other guys on their annual bachelor’s vacation from their wives. Who would have thought on a deserted island, we would run into these guys drinking Pabst Blue Ribbon at 10AM?

At this point, Dustin, Yulia, Matt, Dan and I were all really starting to get to know each other very well.

At night we played games and cooked gourmet meals, laughing and trying our best not to be eaten alive by mosquitos. But we all had our duties on the boat, cleaning the deck, washing dishes, cooking, mixing Painkillers (famous BVI drink made of Rum, crème de coconut, pineapple and orange juice).

After spending ten days at sea, rarely having a formal dock or any of the modern conveniences of a yachtclub—i.e. we had to bath by jumping in the sea, soaping ourselves then rinsing off with the shower on the pool step—everyone agreed to spend our last few days at the Bitter End yacht club on Virgin Gorda.

We could reprovision, take showers, and relax at the club. We had only ten more bikinis to shoot and wanted to finish it up quickly in a couple of hours at the nearby Prickly Pear Island.

The island offered some interesting possibilities, with the abandoned bar, some pebble beaches and palm tree coverage. We didn’t have the pressure of 80 suits looming over us at this point. We had a good working relationship with one another. Also I felt like I had gotten used to the wind, the clouds, possible showers, and other obstacles to shooting. We were able to mostly get away with using two reflectors again except for the first two or three shots in the early morning when the sun had not yet come fully around to our location from behind the mountain of Virgin Gorda.

We banged off our martini shot well before 10 AM, and somehow ended up at the fanciest yacht club I have ever seen called Costa Smeralda.

They even had a valet come fetch us and take us there. We were practically the only guests and had the place to ourselves.

The day could not have been more perfect, except that as I was relaxing by the pool, I learned that my most beloved doggie Charlie, had just passed away.

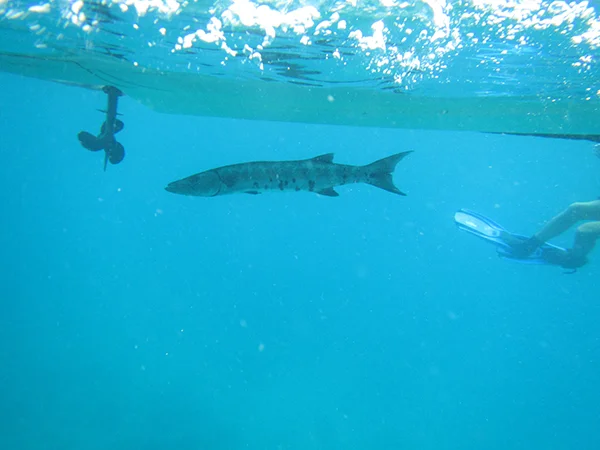

Our last day was spent at Norman Island where we snorkeled at Indians and the Caves, saw sharks, and just fully enjoyed the last moments of our trip.

The following morning, 4:30 AM, sadly and in the rain, we sailed back to Roadtown to return the boat and make our final departure back to Los Angeles.

I did not expect to like the British Virgin Islands as much as I did. I can think of no other place more perfect for a sailing/photoshoot trip—so many islands to visit, countless spectacular landscapes, pristine beaches, crystal clear water, amazing snorkeling and scuba diving, and best of all, lovely, fun and interesting people.

Hello, World!

Natural Lighting

Natural Lighting

Lighting is one of my favorite parts of photography. It is where I feel I have the greatest sense of freedom and creative expression. My favorite kind of lighting is sometimes the simplest of all—natural. I have used natural lighting for catalogues, editorials and portraits. I frequently use photoflex retractable two-sided (silver and white or gold and silver) disk reflectors. And this is because they are super versatile, portable, and give excellent results.

Click the play button on the video below to see me at work using natural lighting on a catalogue shoot for Kain Label.

When I have more time to set up extra equipment to get the lighting just the way I like it, I sometimes use a Scrimjim 6x6 silk in addition to reflectors. The two photos shown below (shot for a beauty editorial for Anna Magazine) were lit with a silk overhead and two silver reflectors.

When I use the reflector as a frontal fill light, I usually use the white side, and when I use it as a highlight, I most often use silver.

I like to take advantage of natural reflections and shadows and just use the reflector to accent the model as seen in this photo to the left.

The reason I prefer an assistant holding the reflector over having it rigged and fixed on a stand is that there is added freedom of movement for both the model and me by having an actual human being there to mimic our movements and continuously adjust the lighting accordingly.

In the best case scenario, I have at least two reflectors held by two assistants at differing angles depending on the sun’s position and the situation. Having at least two reflectors gives a richer, more professional look. Using two reflectors wisely is like having three lights at your disposal (the sun, itself, being the third and strongest light). I always aim to make the sun either the back light or a side light/highlight. If you use the sun as a frontal light, the model will most likely have trouble keeping his or her eyes open. There are rare cases where I may use the sun as a frontal light perhaps in the early morning or late afternoon when the sun is rising or setting. But most likely the lighting will look too harsh, and also it limits your possibilities for positioning the reflectors as reflector light will not be strong enough to act as a highlight for the sun.

If you are in a situation where the sun is very high in the sky and the lighting is very harsh no matter how you position your model, the best option may be to either flag or screen the sun with a silk, or to position the model in the shade somehow—either under a tree or under some kind of structure (as in the photo above, shot under the shade of a tree), sheer curtains (as seen in the photo below), or umbrella.

I have even used a white parachute for the purpose of softening harsh sunlight. Even when shooting in the shade, you can still use reflectors to create an interesting effect as see below (shot while the sun was setting).

I always aim to add depth to my lighting scheme. Flat light is the most boring light, whether it is artificial or natural. It is always nice to maximize the dynamic range in the image by creating highlights and shadows in addition to preserving midtones (that is unless you are intentional trying to achieve a low-contrast effect).

When using natural light, it is also important to remain aware of the position of the sun in the shoot location and to be able to predict which direction it will move as the day progresses. I usually make a tentative shot list depending on the scenery, time of year, and current weather conditions. This doesn’t mean that my plan does not change. As a matter of fact 90% of the time, the plan will change. But it is always best to have a plan, even if the plan must be thrown out the window at some point, due to spontaneous inspiration or unforeseen events.

If you are too attached to your plan, it can be very limiting to creativity. Sometimes decisions must be made quickly on the spot especially if the lighting is changing or not acting as you may have predicted. You may want to shoot against a certain scenery, however, the lighting on the model may not be ideal for shooting there. It may be too windy, or perhaps the model has a really hard time keeping his or her eyes open. I would choose the model's comfort over good lighting any day. If the model looks tense or uncomfortable, chances of capturing a good image are very low. So you must quickly find another option that is more comfortable and also has acceptable lighting for the model.

I love shooting directly into the sun. It gives the photos a bit of whimsy and lightness, like when a child looks up into the trees and has a sense of wonder at the light speckling through the fluttering leaves. It adds a sense of motion and emotion to the image.

Using reflectors as opposed to lights has many benefits: (1) you can see what the light is actually doing much easier than when working with strobes, (2) you can shoot more frames per second (strobes have a slower recycle time) this is especially handing when shooting a model in action, (3) you can move from location to location with more ease as reflectors are more lightweight and portable, (4) you save physical energy and have more freedom to experiment and be creative, (5) there is easier access to difficult to access or tight squeeze locations that might be otherwise prohibitive with cumbersome equipment.

On an extremely overcast day, natural lighting can be the most challenging, but it is still possible to make it interesting. I often aim for a low contrast look or a blown out look in this situation.

Sometimes if the weather is really dreary, I just cave in and pull out my Canon 600 EX-RT flash and use it as a fill, or I use a portable unit such as a Quantum 400 or a Profoto 7B as a side or back light to make it appear like the light has more dimension.

I have even shot a catalog in the pouring rain once because the client could not cancel due to time constrictions and they insisted on shooting outdoors as planned. This was probably one of the most challenging situations I have ever faced, but I just pulled out my Quantum 400s and several umbrellas for protection from the rain, and did the best I could creating a moody effect.

Hazy days can offer the best lighting possibilities (as seen in three photos below). It is like having a large silk over the sun, softening the light just right and also making it possible to still reflect a good amount of light. This condition can be very interesting for lighting, but unfortunately, it is not as frequent as we might like in Los Angeles.

More often we have days when the light appears in and out from behind the clouds. This can be annoying because just as you have chosen your camera settings, the light changes again. What I do in these situations is have two separate camera settings (shutter speed, aperture, and ISO)—one for full sun and one for when the sun is hidden behind the clouds. This way I can quickly toggle back and forth as the sun goes in and out.

Sometimes I like to use natural light diffused through a window or skylight (as seen in the first three photos below). Just because the light is diffused doesn't mean you cannot reflect it. This light can be very soft and flattering, but the depth of field will be very shallow because it is basically a low light condition.

Or if you position the model at a greater distance from the light source, you can create a darker moodier effect (as seen in the four photos below).

One drawback to shooting with natural lighting and reflectors and silks outdoors can be the wind. Often shooting on the beach or in the desert, there can be strong wind, and it can be difficult for one assistant to manage holding a reflector in place. Sometimes the assistant will have to use his/her feet in addition to his/her hands to hold it in place or use a c-stand and a couple of sandbags. I have even thrown some sand onto the bottom to weigh the reflector down, if I want more freedom to move. Sometimes it may be necessary to have two assistants hold one reflector to keep it in the right position. In extreme cases assistants must use all four limbs and body weight to control the reflector in the wind. But keeping the light in the right place and having an assistant who can see the light moving and judge based on your directions is absolutely key to getting the desired results.

In any case, using natural light always requires adaptability and resourcefulness no matter what. But that is exactly what makes it more fun, creative, challenging and often rewarding in the end, and why it is my favorite lighting to work with.

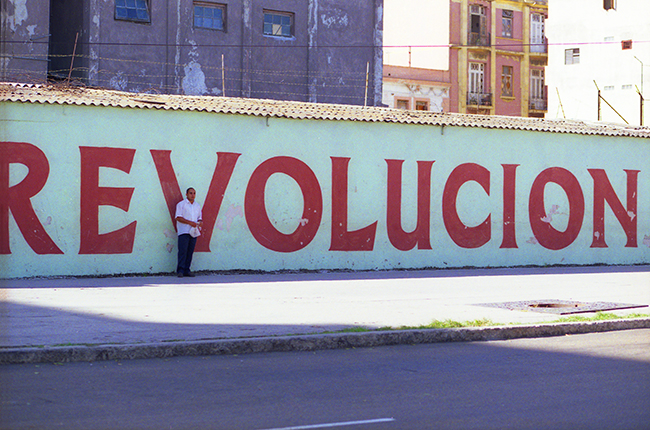

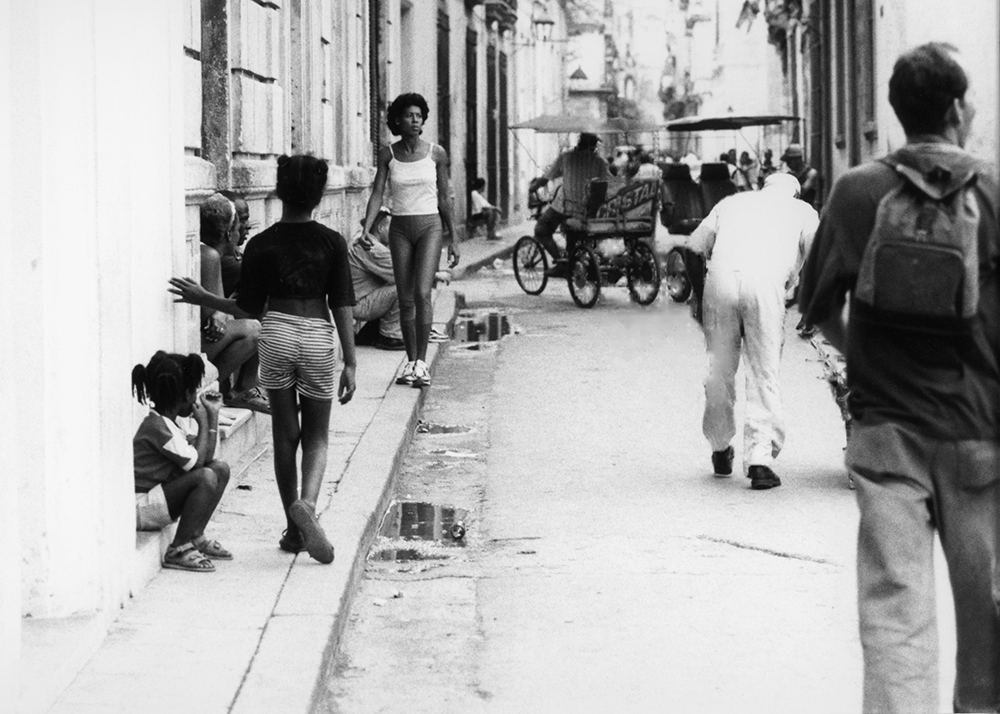

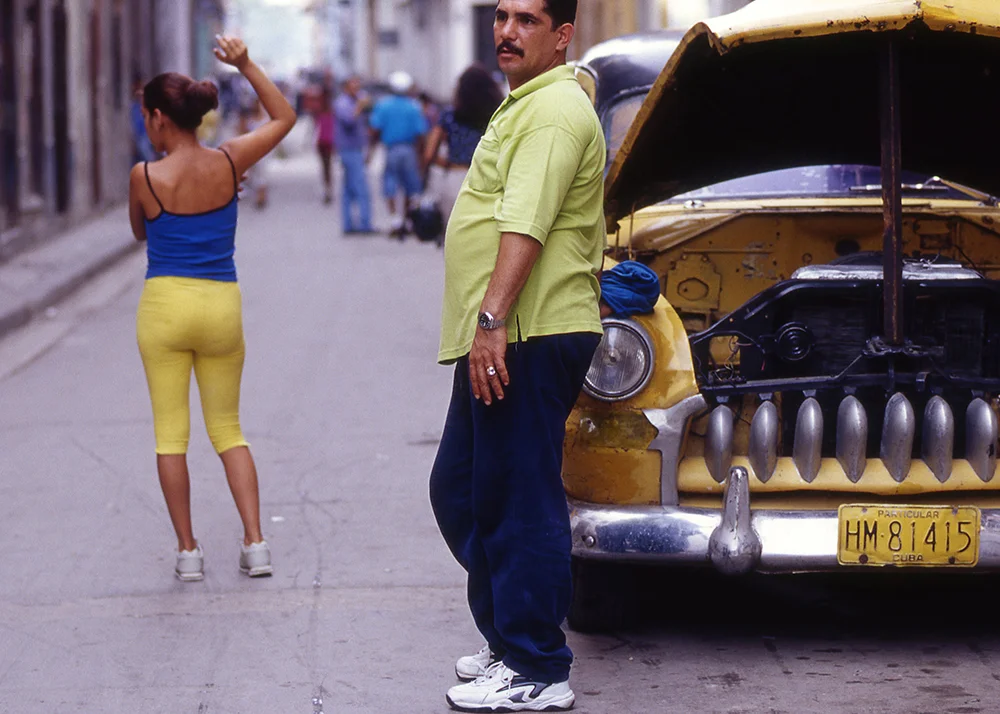

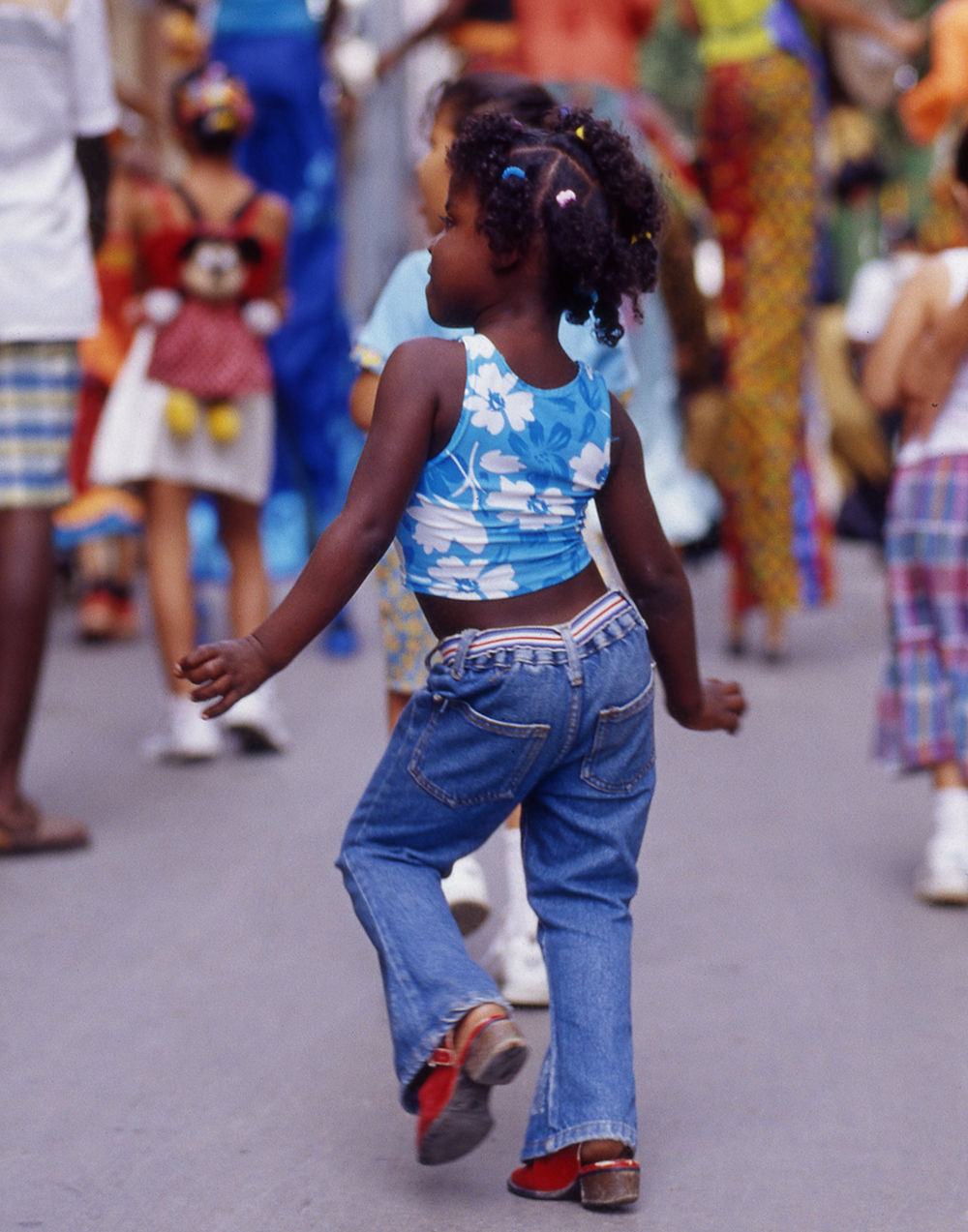

Havana Adventure 2001

Travel Photography

Havana, Cuba

Havana Adventure 2001

In November 2001, Frank and I traveled to Havana, Cuba. Our trip resulted mostly from my own curiosity and sense of adventure. For those of you who know Frank, traveling to a communist country would definitely not be high on his agenda, but at this point in our relationship, I think he would have done anything I had asked of him. My imagination was fueled by Ernest Hemingway and movies like I am Cuba, Before Night Falls, and Strawberry and Chocolate. I also had cultivated an absolute love affair with Cuban music after years of listening to Tom Schnabel’s radio show on KCRW.

We had to travel through Cancun, Mexico since the United States has had an active embargo against Cuba since 1960. We stocked up on American dollars—ironically, the main currency in Cuba—and boarded an Aeroflot flight (Russian operated) bound for Havana. Barring the smoke that filled the cabin halfway through the flight, we somehow arrived safely. The courteous customs officer neglected to stamp our U.S. passports and instead issued us a piece of paper which was later collected upon our departure.

Armed with my Canon EOS 1N and 24/1.8, 50/1.4, 85/1.8 lenses, I was determined to document this trip, using a mixture of Tri-X 400, Ektachrome 100, and Kodak Gold 200. In 2001, most photographers, myself included, were still leery of the digital revolution.

We had no hotel reservations, which if you know Frank, could be a catastrophic event. But it was impossible to email or get through to anyone on the telephone before our departure due to U.S. embargo. So we had no other choice but to take our chances. My actor friend, Seymour Cassel, who had been to Cuba several times, had assured me how inexpensive it was, telling me that hotels ran about $50 per night—a gross underestimate! The first hotel we wandered into, the Golden Tulip, wanted $400 per night! We ended up in a small French operated boutique hotel called Conde de Villanueva located in the heart of Havana Viejo for a measly $200 per night—still exceeding out budget by 400%! Long story short, we knew early on that we did not bring enough cash with us and would never last the full two weeks we had planned to stay. As any American who has been to Cuba knows, it is impossible to draw or receive cash in any form once in Cuba. We spent countless hours and hundreds of dollars on the telephone and visiting the Western Union office trying to get our European friends to wire us money without success.

We walked about a mile to save $1 on cab fare (we were on a strict budget) to go to the airport ticket counter and try and change our tickets to leave sooner. While standing in the taxi cue composed of all vintage American vehicles (pre-1960), we encountered a very savvy street hustler named Juan. Frank immediately took a liking to him because Juan was ambitious and charming and no doubt reminded Frank of himself as a young man. Juan tried to negotiate a cab fare for us with several taxis, and Frank ended up inviting him to come along with us for the ride. It is a law in Cuba that all drivers must pick up hitchhikers, so we accumulated more company on this ride than expected. At one point, there were at least 7 of us squeezed into the spacious back seat of a 1957 Chevy. Rapid Spanish firing all around us, Frank and I looked at each other and just laughed.

Well, we never made it to the airport ticket office that day. There was a anti-American demonstration happening, one which all Cuban citizens were “required” to attend. The demonstration was to protest the injustice of the death of some Cubans who had attempted to escape on a raft and had died before reaching Florida. The streets were filled because people were given the day off of work and penalized (so we were told) if they didn’t show up.

Cubans are strictly prohibited from socializing with white tourists. They could be arrested because authorities feared they might try to defect. Because of this Juan was careful to walk a two or three feet behind us so as not to draw attention from the men with machine guns standing on most street corners in the center. Juan took us on a tour of the less travelled parts of the city and told us about his life. He told us that he made $10 per week as an accountant and confessed that most Cubans, himself included, could not wait for Castro to die because they dreamed Cuba would some day finally become part of the United States like Puerto Rico so all their problems would be solved. We treated Juan to more than a few mojitos and shared many laughs, even though it appeared we were suddenly being charged double price for the drinks.

Juan insisted that we come to his home for dinner that night. The building in which he lived had an exquisite view of the state capitol. In a normal economy, that location would have cost a fortune. Unfortunately, there was no running water or electricity, since the building was in a shambles and all the residents were squatting. His wife, eight months pregnant, served us an seven course typical Cuban meal, cooked on a small propane stovetop, while some other male residents lifted weights on the veranda downstairs. Kool and the Gang’s “Fresh” played on a portable boom box in the background. We shared at least two 750 ml bottles of Havana Club Anejo Especial Rum, sipping directly from the bottle, while watching the sunset.

Frank and I both understood, at this moment, even though the trip did not turn out as expected, we could not hope for a better experience—connecting with Juan and his family and having the opportunity to share part of their daily existence in a world so close, yet so distant from ours (about 100 miles from the U.S.). Later, we drunkenly made our way into Havana Viejo to listen to a killer salsa band playing at a corner café. We danced among all ages—toddlers to seniors.

The next morning, we both woke in a rum-induced daze. I searched through my pockets and counted our financial reserves stashed in the hotel safe, quickly coming to the realization that after settling our hotel bill, we would be left with less than $100—that is if we left that day. I told Frank, “don’t worry, we can wash dishes if we have to!” He was clearly in a panic. “Well, as a last resort, one of us can fly back to Mexico, get more money, and come back and pay the hotel bill,” I reasoned. I quickly realized that this did not settle his anxieties.

“I grew up poor and have no desire to repeat the experience,” he warned.

Somehow we made it to the ticket counter and managed to change our flight and left the following day. We boarded the plane to Cancun with less than two U.S. dollars in our pockets. As soon as we hit Mexican soil, Frank made a point to hit as many ATM’s as possible before we even reached the hotel.

We didn’t get to see the Cuban countryside as we had planned. Two of the four boxes of Cuban cigars I had bought for my father were confiscated at Mexican border. But none of that made any difference. Havana was one of the most delightful experiences we could have hoped for. We saw some of the most dire living conditions. I really got the sense that the people felt trapped and oppressed. However, they refused to let their spirit be defeated and continued to engage fully in life—dancing, singing and loving life.

I had a wonderful experience photographing the people of Havana. Many of them loved having their photos taken and even offered to pose for me.

I hope I will have the pleasure to return to Havana some day. It was all I had imagined and much, much more.